|

By Ken Baker, Board Consultant - Upper Arkansas Water Conservancy District The Colorado General Assembly convened on January 4, and the Upper Arkansas Water Conservancy District is closely monitoring water-related legislation. I have highlighted in our January legislative update below, some of the issues being considered by state legislators that we are following. In the coming months, I will continue to update you on their progress and in the meantime, I hope that you find our legislative updates beneficial and informative. The State Plan

The Colorado Governor’s Office has promoted a bill called The State Plan. The plan is basically a theme to develop a water sharing program in which agricultural water rights would be changed to municipal use to be exported to the northern front range of Colorado to supply future water needs of an anticipated population growth. The plan does not contain specifics with respect to water uses to be changed, but at the same time does not specifically include water resources available on the northern front range. Encourage Use of Xeriscape In recent years the General Assembly has passed laws limiting the authority of homeowner’s associations requirements to plant lawns. A current bill will encourage the use of xeriscape in Common Areas. The Upper District will encourage such water rationing promotions. Water exports from rivers in Division No. 2 and Division No. 5 have historically been sources of the historic consumptive use of agricultural appropriations to be transferred to the northern front range. Rationing of water uses within the municipal uses may not represent a complete answer to resolution of water supplies under The State Plan, but it could represent some relief for water managers in the front range communities and in the mountain river valleys asked to satisfy the objectives of The State Plan. Wildfire Mitigation Senate Bill 037 is being introduced to authorize the county commissioners or a private not-for-profit organization to clear the State or Federal lands, within the county, from materials that represent fire hazards. The County of Chaffee has a voter approved tax revenue base to support this proposition. The bill as presented protects the County from liability, unless an employee is negligent or willful in creating damage. The Upper District, through a blanket augmentation plan, provides water resources to address fire hazard prevention projects. The District supports the bill introduced in the Senate. Concerning the Rights of a Water Rights Easement Holder This bill is prompted by ditch owners who want to clear trees along the ditch right-of-way. The bill provides a right to line the ditch to prevent seepage. This could include a pipe in the ditch. Some of the objections to the bill include Amended Rules and Regulations created by Court order to protect return flow rights of the State of Kansas in the Arkansas River under the 1948 Treaty Agreement. A special committee of the CWC State Affairs Committee has been appointed to review and clarify language in the bill. Concerning the Protection of Water Quality from Adverse Impacts Caused by Mineral Mining This bill was presented last year and then withdrawn. The bill is complex. There should be continued discussion on bill language, the roles of water quality and mining entities need to be better defined.

0 Comments

by Blake Osborn - Southern Colorado Water Resources Specialist for the Colorado Water Institute and CSU Extension Think back to 3rd grade. Remember learning about the water cycle? It looked good on paper, didn’t it? Water moves through different environments (the soil, plants, atmosphere, streams) and it all ends up in the ocean. Well, in Colorado we’re a long way from an ocean. We are best characterized as a “headwaters” environment. With Mother Nature’s help, we are given a certain amount of water every year, a budget, if-you-will. It’s our job as water users and water stewards to make the best use of this water, all within the framework of our administrative king-pin called the Prior Appropriation Doctrine.  As scientists, we use a number of different tools and methods to estimate the amount of water in each of the different environments. How much water is in the soil? How much is left in the mountain snow fields? When will it melt, and what is the streamflow going to be? Further, these questions can be broken down into more nuanced questions like ‘how much water is within the plant’s rooting zone, and how much is below the root zone and “immune” to evaporation?’ If we are to make the best use of our water we need to know exactly where the water is located and how much is there.

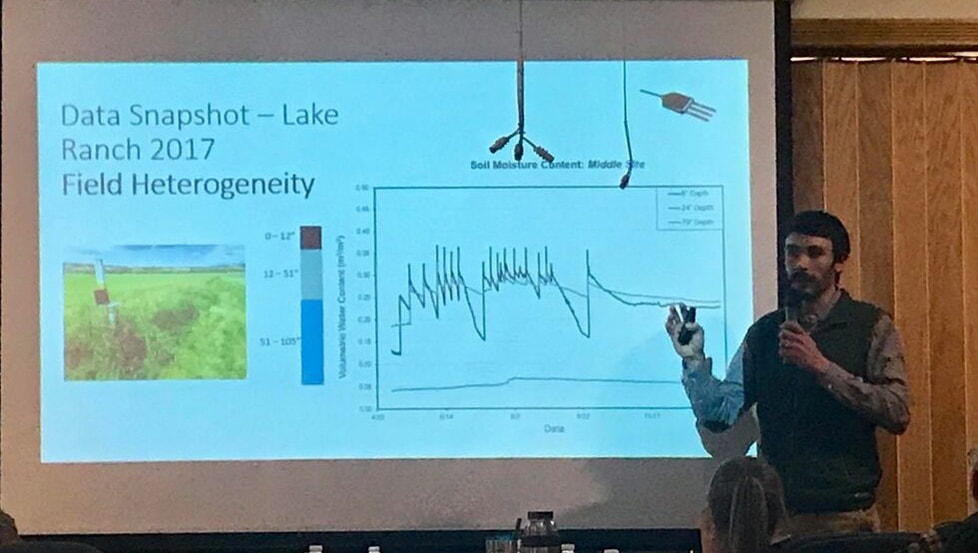

As the largest water user in the state, agricultural water use is necessary to support one of our worst habits: eating. How nice would it be to not have to eat? Some would argue with that statement, as eating can be a great pleasure, but it also requires a lot of inputs like water and land. And that’s OK. It’s just the nature of growing food. Because agriculture uses a lot of water, it is often difficult to know exactly how much water is applied and how much is needed. It is entirely possible that we over irrigate our crops in certain times of the year, and under irrigate in other times. Almost all farmers do the best they can to make the best use of irrigation water, but the timing and amount of water available to them is very dynamic. This is a great challenge facing farmers around the world, but new tools are being developed to help make projections about the water demands of local crops that are cost-effective and easy to use. Currently, a research project between Colorado State University and the Upper Arkansas Water Conservancy District is trying to get a better grip on some of the questions from above. The movement of water between one environment and another, also called water fluxes, are being measured over a three year period to better understand how water availability, environmental conditions, and management decisions impact water use in agriculture. Instruments are set-up in four agricultural fields, from Buena Vista to Westcliffe, to measure things like precipitation, evaporation, and soil moisture changes. This important data can be used to more accurately estimate the amount of water agriculture is using in the region, inform water users where efficiencies might be possible through enhanced management, and help to develop irrigation scheduling tools to give farmers cost-effective and accurate data to make these decisions. Although we are in the middle of data collection and data processing, this research project has already uncovered some interesting results. First, if water is not a limiting factor and farmers are able to irrigate freely, they typically apply water in uniformity across the field. However, field and crop water demands can very highly variable within a field and applying water uniformly significantly impacts the efficiency of a system. This is called the “1 field, 1 number” concept. A farmer might irrigate their entire field based on the driest spot in the field, and if that spot needs 2.5 inches of water every week, then the entire field will get 2.5 inches of water every week, even if 75% of the field only needs 1.8 inches. This is entirely reasonable and a smart business decision on the part of the farmer. A big reason for this is that farmers are limited in their management decisions because irrigation technology is not flexible enough, or not cost effective, to apply water through precision agriculture. In short, understanding field conditions and how they impact the amount of water available to plants could be one of the biggest data gaps that is limiting the efficient application of water. Another interesting finding from this study is the significant impact “sub-irrigation” has on high-mountain flood irrigated hay fields, particularly in the Wet Mountain Valley. Sub-irrigation has long been known as an important factor for growing hay in this region, but the timing and duration of the sub-irrigation is significant, even during extreme drought years. Not surprisingly, fields located near streams are more susceptible to changes in sub-irrigation compared with fields not near streams. One field site, located within feet of Taylor Creek, showed greater decreases in sub-surface soil moisture compared with a field site located nearly a mile from a stream. This surface-groundwater connection is vitally important in most regions, but is especially true in flood irrigated regions like the Wet Mountain Valley. With 1 more year of data collection and data processing we are sure to uncover more information that can help to lead to more informed management decisions. It is much easier to manage something as important as water when we have a good understanding, and good data, to support our decision making. This partnership between the Upper Arkansas Water Conservancy District and Colorado State University is working to acquire this data, and use it to make better management decisions. The Arkansas River Basin is only given so much water each year, how we use and manage that water is critical to sustain healthy ecosystems, farming economies, and our cultural identities. This time of year, Colorado’s water leaders meet in Denver at the annual Colorado Water Congress convention. Water managers, attorneys, engineers, board members of the State’s water conservation and conservancy districts, and State water officials convene around an agenda that includes the latest conversation on current water issues, projects, new concepts to optimize water use and legislative initiatives. How the new State administration may deal with the water plan will be on everyone’s mind. New concepts of water appropriation and administration will be discussed with pro and con debate. These concepts will continue to revolve around alternative transfer methods and the perennial discussion over drought and the prospect of drought. The culture of water use and drought are intermingled in the spirit of the West. The aridity of the Western USA is a constant condition in the thoughts of water users. I believe it is appropriate for our readers to ponder the following poem written over 70 years ago by arguably the greatest American poet, Robert Frost. Robert Frost was a farmer and he understood the dependence upon vagaries of weather that agriculturalists face. THE BROKEN DROUGHT

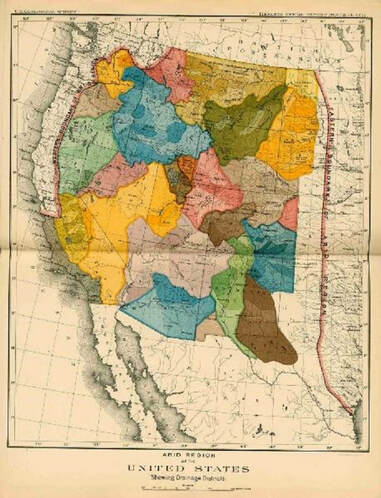

By: Robert Frost The prophet of disaster ceased to shout. Something was going right outside the hall. A rain, though stingy, had begun to fall That rather hurt his theory of the drought And all the great convention was about. A cheer went up that shook the mottoed wall. He did as Shakespeare says, you may recall, Good orators will do when they are out. Yet in his heart he was unshaken sure The drought was one no spit of rain could cure. It was the drought of deserts. Earth would soon Be uninhabitable as the moon. What for that matter had it ever been? Who advised man to come and live therein? A veteran of the Civil War, John Wesley Powell, began the exploration of the arid west in 1869 to analyze its unique characteristics. At the time the Western United States was comprised of a group of territories in a landscape much of which was devoid of the lush vegetation characteristic of the Eastern part of the North American continent. This land—the Great American Desert—created developmental challenges for the US Government. Unlike the East and Mid-West water was scarce and an intricate system of water diversions and distribution canals was necessary to develop these territories into productive regions. Yet in 1890 a report from Powell to the Senate Select Committee on Irrigation and Reclamation of Arid Lands fell on deaf ears. Based upon Powell’s accumulation of data and findings from earlier western lands explorations he recommended the development of political jurisdictions based on hydrologic divides or watersheds. He was ignored, and states were created along arbitrary boundaries devoid of any natural physical land characteristic. It would take nearly 50 years before Powell’s recommendations would be instituted, but not from the Federal Government.  Powell’s map on the left depicted with jurisdictions bounded by natural hydrologic features. Water drainages would have political jurisdictions distinctly divided by natural water courses and their corresponding water sources. Colorado, a headwaters state which sends water to all the arid regions of the west, was the first to develop legislation authorizing the creation of political subdivisions designed to have jurisdiction over watershed regions. Powell’s recommendation would take root within a state under the legislative authority of the Water Conservancy Act. The Upper Arkansas Water Conservancy District is one of these entities.

The Water Conservancy Act was adopted by Colorado in 1935. It charges these water districts with the responsibility to do “Works” as defined in the statute. These Works are the development of water and power resources both physical and intangible. Some of the physical structures are reservoirs and water diversions to supply water for irrigation, municipal, industrial and other uses within its jurisdiction. Intangible assets may be accumulated data on weather and stream flows, acquisition of decrees for water rights, or the creation of augmentation plans that cover large portions of a watershed. Other political subdivisions, such as counties do not have the jurisdictional authority to conduct water activities, and because their boundaries are arbitrary and do not necessarily follow hydrologic divides, which are essential to the accomplishment of major water works. Since revenues obtained by political subdivisions must be utilized for the benefit of the citizens within that division, these revenues cannot be used to benefit a part of a watershed outside the political subdivision. Likewise, the authority to direct the use of these revenues outside a political subdivision is lacking. For example, funds spent on a project inside a county generated from a levy upon the citizens of that county cannot be utilized to benefit the watershed outside of that county. Powell recognized this reality although on a larger scale. Water Conservancy Districts undertake watershed-wide projects authorized through the Water Conservancy Act. One of the present conundrums being discussed by some entities is how to undertake basin-wide projects—such as forest health and stream management projects. The clear answer lies in the Water Conservancy Act. It is through Water Conservancy Districts with basin-wide jurisdiction that these projects can be undertaken. Some recent articles have been written about large scale projects of the Upper Arkansas Water Conservancy District that create benefits for large portions of the Upper Arkansas watershed. The District has the jurisdictional authority to utilize revenue from various sources including its own revenue sources and match the revenue source commensurate with a localized benefit. On a smaller scale the District has undertaken integrated water management projects with municipalities on tributary drainages such as the South Arkansas River. On a larger scale the District’s Umbrella Augmentation Plan crosses several counties, all within the same watershed. The District can combine cost share funds from several political subdivisions with state and federal grants. Other entities lack these abilities either because they lack specific legal authority or are unable to expend funds for benefits outside their jurisdictions. As the population of the Arkansas Basin increases the challenges of providing adequate clean water supplies will increase. It is comforting to know and understand that these challenges can be met by good planning and actions of our Water Conservancy Districts. In the Upper Arkansas watershed that entity is the Upper Arkansas Water Conservancy District. You can learn more about our projects at www.uawcd.com or by contacting the District and finding out about our Water Talks education program. |

ABOUTLocal water news by the Upper Arkansas Water Conservancy District Archives

August 2023

Categories |

CONNECT |

|

UAWCD Technology Accessibility Statement

UAWCD is committed to providing equitable access to our services to all Coloradans.

Our ongoing accessibility effort works towards being in line with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) version 2.1, level AA criteria. These guidelines not only help make technology accessible to users with sensory, cognitive and mobility disabilities, but ultimately to all users, regardless of ability.

Our efforts are just part of a meaningful change in making all State of Colorado and local government services inclusive and accessible. We welcome comments on how to improve our technology’s accessibility for users with disabilities and for requests for accommodations to any UAWCD services.

Requests for accommodations and feedback

We welcome your requests for accommodations and feedback about the accessibility of UAWCD’s online services. Please let us know if you encounter accessibility barriers. UAWCD is committed to responding as quickly as possible.

E-mail: [email protected]

Mail: P.O. Box 1090, Salida, CO 81201

Phone: 719-539-5425 (Written requests are preferred. If you are unable to submit your request in writing, you are welcome to contact us by telephone at this number.)

UAWCD is committed to providing equitable access to our services to all Coloradans.

Our ongoing accessibility effort works towards being in line with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) version 2.1, level AA criteria. These guidelines not only help make technology accessible to users with sensory, cognitive and mobility disabilities, but ultimately to all users, regardless of ability.

Our efforts are just part of a meaningful change in making all State of Colorado and local government services inclusive and accessible. We welcome comments on how to improve our technology’s accessibility for users with disabilities and for requests for accommodations to any UAWCD services.

Requests for accommodations and feedback

We welcome your requests for accommodations and feedback about the accessibility of UAWCD’s online services. Please let us know if you encounter accessibility barriers. UAWCD is committed to responding as quickly as possible.

E-mail: [email protected]

Mail: P.O. Box 1090, Salida, CO 81201

Phone: 719-539-5425 (Written requests are preferred. If you are unable to submit your request in writing, you are welcome to contact us by telephone at this number.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed